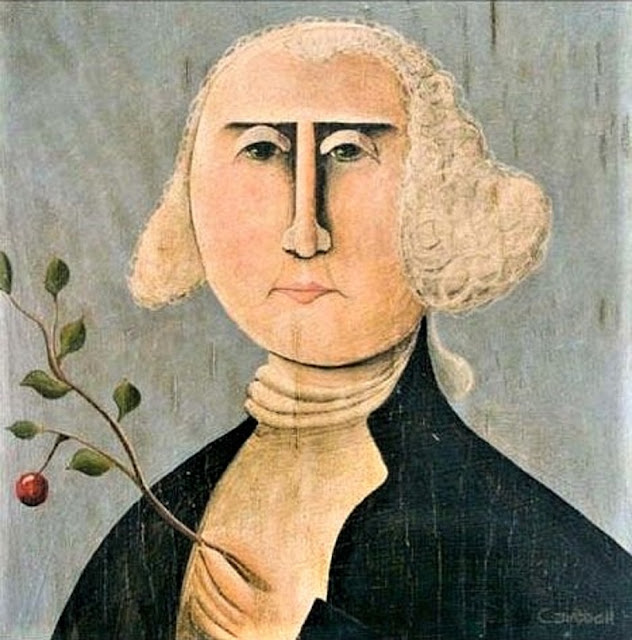

George Washington by contemporary artist Tim Campbell

For centuries, people visited the Berkeley Springs area in the northeast corner of what is now West Virginia, to enjoy the health benefits of the warm mineral waters that flow from local springs at a constant temperature of 74.3°F. Reportedly Native Americans from as far away as Canada, the Great Lakes, & the Carolinas traveled to bathe there.

In the mid 1700s, George Washington, who first visited at age 16, was a regular visitor and spread word of the waters, helping establish Berkeley Springs' reputation as a health resort throughout the American colonies. One of the earliest sources showing an appreciation of mineral waters for bathing in the new world is a 1748 reference in George Washington’s diary to the

“fam’d Warm Springs.” At that time only open ground surrounded the springs which were located within a dense forest.

Before the Revolution raged, General George Washington found time to share in the development of Berkeley Springs. Here, where mineral springs still maintain a flow of 1500 gallons a minute at 74 drgrees must have been unaware-or simply not interested-that, late in the 18C, itinerant evangelists denounced the place as a

"Seat of Sin" for its horse racing, gambling, and other ungodly revelries.

Here rude log huts, board and canvas tents, and even covered wagons, served as lodging rooms, while every party brought its own substantial provisions of flour, meat and bacon, depending for lighter articles of diet on the local “Hill folk,” or the success of their own foragers.

A large hollow scooped in the sand, surrounded by a screen of pine brush, was the only bathing-house; and this was used alternately by ladies and gentlemen. The time set apart for the ladies was announced by a blast on a long tin horn, at which signal all of the opposite sex retired to a prescribed distance, ... Here day and night passed in a round of eating and drinking, bathing, fiddling, dancing, and reveling. Gaming was carried to a great excess and horse-racing was a daily amusement.

George Washington, a 16-year-old apprentice surveyor, describes Warm Springs, now called Bath or Berkeley Springs, in Morgan County, W.V. in

A Journal of my Journey over the Mountains. [March 1748]

;Fryday 18th. We Travell’d up about 35 Miles to Thomas Barwicks on Potomack where we found the River so excessively high by Reason of the Great Rains that had fallen up about the Allegany Mountains as they told us which was then bringing down the melted Snow & that it would not be fordable for severall Days it was then above Six foot Higher than usual & was Rising. We agreed to stay till Monday. We this day call’d to see the Fam’d Warm Springs. We camped out in the field this Night.

Martha Washington by contemporary artist Tim Campbell

In 1761, Washington was in Winchester until after the election on 18 May and apparently returned to Mount Vernon ill. Martha Washington wrote Margaret Green on 26 June,

“Mr W—n took his vomit—but it did not worke him well to-day he has began with the Bark and continues it till an ounce is taken.;" In late August, he went to the Warm Springs in Frederick County, and in a stay of several weeks his health improved, though he had a relapse in October and November.

A letter from George Washington to Charles Green, 26–30 August 1761 On Warm Springs [Va.]

Revd Sir

I shoud think myself very inexcusable were I to omit so good an oppertunity as Mr Douglass’s return from these Springs, of giving you some Account of the place, and of Our Approaches to it.1

To begin then—We arrivd here yesterday, and our Journey (as you may imagine) was not of the most agreable sort, through such Weather & such Roads as we had to encounter; these last for 20 or 25 Miles from hence are almost impassable for Carriages; not so much from the Mountainous Country (but this in fact is very rugged) as from Trees that have fallen across the Road, and renderd the ways intolerable.

We found of both sexes about 2⟨5⟩0 People at this place, full of all manner of diseases & Complaints; some of which are much benefitted, while others find no relief from the Water’s—two or three Doctors are here, but whether attending as Physicians or to Drink of the Waters I know not—It is thought the Springs will soon begin to loose there Virtues, and the Weather get too cold for People, not well provided, to remain here—They are situated very badly on the East side of a steep Mountain, and Inclosed by Hills on all Sides, so that the Afternoon’s Sun is hid by 4 Oclock and the Fogs hang over us till 9 or 10 wch occasion’s great Damps and the Mornings and Evenings to be cool.

The Place I am told, and indeed have found it so already, is supplyed with Provisions of all kinds—good Beef & venison, fine Veal, Lamb, Fowls &ca may be bought at almost any time; but Lodgings can be had on no Terms but building for them, and I am of opinion that numbers get more hurt by there manner of lying, than the Waters can do them good—had we not succeeded in getting a Tent & marquee from Winchester we shoud have been in a most miserable situation here.

In regard to myself I must beg leave to say, that I was much overcome with the fatigue of the Ride & Weather together—however I think my Fevers are a good deal abated, althô my Pains grow rather worse, & my sleep equally disturbd; what effect the Waters may have upon me I cant say at present, but I expect Nothing from the Air—this certainly must be unwholesome—I purpose to stay here a fortnight & longer if benefitted.

I shall attempt to give you the best discription I can of the Stages to this place, that you may be at no loss, if after this Acct, you choose to come up. Toulston I shoud recommend as the first, Majr Hamilton’s, or Israel Thompson’s the 2d; the one abt 30, the other 35 Miles distant; from thence you may reach Henry Vanmeter’s on Opeckon Creek, or Captn Paris’s 4 Miles on this Side, which will be also abt 35 Miles; and then your Journey will be easy the following day to this place.2

I have made out a very long, and a very dirty Letter, but my hurry must apologize for the Latter &, I hope your goodness will excuse the former—please to make my Complimts acceptable to Mrs Gr⟨ee⟩n and Miss Bolan, & be assurd Revd Sir that with a true respect I remain yr Most Obedt & Obligd

Go: Washington

P.S. If I coud be upon any certainty of yr comg, or, coud g⟨et⟩ only 4 days previous notice of yr arrival I woud get a House built such as are here erected very indifferent indeed they are thô for yr receptn.

30th Augt

Since writing the above Mr Douglass lost his Horses & was dataind, but I met with a Fairfax Man returng home, who is to be back again immediately for his wife. this Person I have hird to carry some Letters to Mrs Washn undr whose cover this goes; by him you are furnish⟨ed⟩ with an oppertunity of honouring me with yr Commands, if you retain any thoughts of comg to this place—I think myself benefitted by the Water’s, and am not witht hopes of their making a cure of me—a little time will shew no⟨w⟩.

Another Washington journal entry for July 31, 1769, records his departure with Mrs. Washington for these springs in West Virginia, where they stayed more than a month. They were accompanied by her daughter, Patsy Custis, who was probably taken in hope of curing a form of epilepsy with which she was afflicted.

In 1775, George Washington took command of New England troops who had been fighting the American Revolution's opening battles and now surrounded Boston to keep the British cooped up there. The newly named American commander found his army an unruly gathering of restless young men in generally filthy and unhealthy camps. He wrote many letters to Congress about the need to change this situation before disease struck and, in one, approved of his men bathing in the Charles River. But, when it came to their

"running about naked upon the Bridge, whilst . . . Ladies of the first fashion in the neighborhood, are passing over it," the general put his foot down.

Washington was certain that troops needed washing whenever the chance for it came.

"While you halt," he wrote in orders to a colonel under his command,

"you will take every measure for refreshing your Men and rendering them as comfortable as you can. Bathing themselves moderately and washing their Cloathes are of infinite Service."

But apparently more than bathing in the medicinal waters was happening at Warm Springs. New England school teacher tutoring in 18C Virginia & keeping a journal, Philip Vickers Fithian wrote of his visit to the springs in 1775,

“In our dining Room Companies at Cards, Five & forty, Whist, Alfours, Callico-Betty &c. I walked out among the Bushes here also was—Amusements in all Shapes, & in high Degrees, are constantly taking Place among so promiscuous Company.” In 1776, America’s first Methodist bishop, Francis Asbury, stated that he was horrified by Bath’s

“overflowing tide of immorality.” After the Revolution in the latter part of the 18C, hundreds of visitors annually flocked to these springs. Although the accommodations were a little less primitive, the cleanliness & therapeutic aims for visiting these waters were very quickly combined with a growing social life surrounding the springs on dry land.

Advertisements for mineral springs usually contained claims for improvement of health in addition to the more obvious social enticements. In 1811, the owner claimed that the waters at Chalybeate Springs in Virginia, "have been inspected by a number of medical gentlemen, both of the city and country, and are admitted to be equal if not superior in their medical and healing qualities to any of the kind ever discovered in America, or perhaps in the world. Liquors of the best kind will be provided and entertainment as good as the country and the season will permit."

Advertisements for mineral springs usually contained claims for improvement of health in addition to the more obvious social enticements. In 1811, the owner claimed that the waters at Chalybeate Springs in Virginia, "have been inspected by a number of medical gentlemen, both of the city and country, and are admitted to be equal if not superior in their medical and healing qualities to any of the kind ever discovered in America, or perhaps in the world. Liquors of the best kind will be provided and entertainment as good as the country and the season will permit."