Guest Blog -

"Pleasure Gardens, Without Worry, In The City"

Harry Kyriakodis

“There is nothing more conducive to the health of a populous city, than free circulation of air, and in this respect Philadelphia is pre-eminently fortunate.” These words appear in Philadelphia in 1830: or, A Brief Account of the Various Institutions and Public Objects in This Metropolis.

William Penn 1644-1718

The Philadelphia guide book briefly describes the 5 public commons that William Penn incorporated into his plan for his “Greene County Towne” -- namely, Penn (formerly Centre) Square, Washington (South East) Square, Franklin (North East) Square, Rittenhouse (South West) Square, and Logan (North West) Square.

William Penn's Greene County Towne Plan for Philadelphia

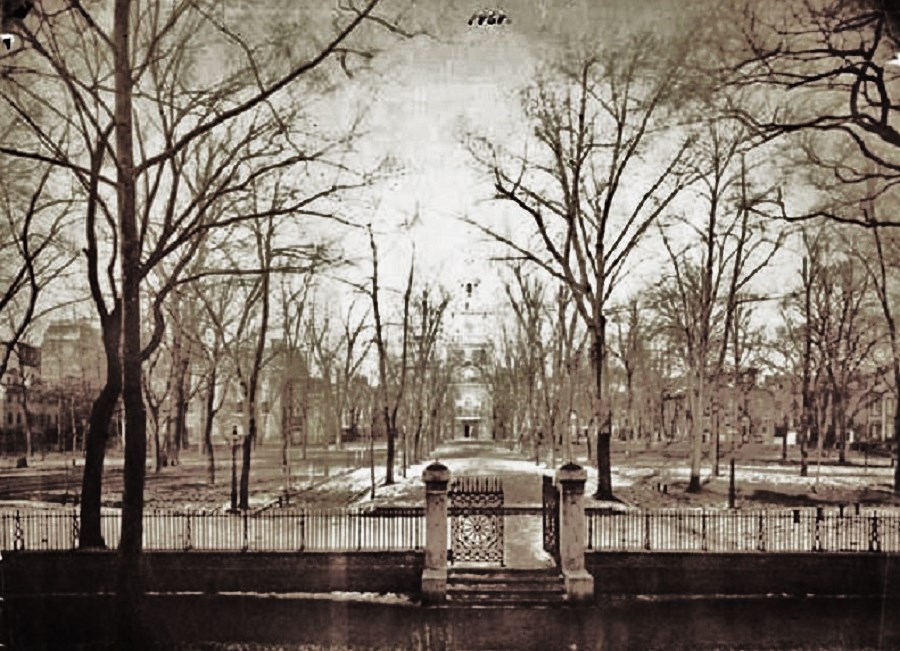

The 1830 Philadelphia guide book also characterizes Independence Square as “enclosed by a substantial iron railing, and planted with trees; the walks are tastefully laid out and gravelled—it is thrown open to the public, and as a promenade, is a place of general resort.”

1868 View of Independence Square

Philadelphia in 1830 was issued long before Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park had been conceived. And the Philadelphia Zoo would not open until 1874. Even the individual park spaces that today make up a good bit of Fairmount Park are not described, as they had not been established as public spaces by 1830. In that era, Philadelphia was only 2 miles wide between South and Vine Streets and the settled portion extended westward to about Broad Street.

The 1830 booklet, however, does describe 3 privately-owned pleasure gardens west of Broad Street that could be enjoyed as “general resorts”—for a fee: McArran’s Garden; Smith’s Labyrinth Garden; and Sans Souci Garden. These were the big botanical resorts located in what is today the western part of Center City. They offered Philadelphians of the early 19C a carefree and manicured respite, all pretty much in what was then the middle of no place. Before the city’s industrialization made Fairmount Park a necessity for personal health and to relieve the city of its harshness, these places were where regular folks, for a price, could spend some time in elegant outdoor surroundings.

Not only was the unsettled area west of Broad Street the location of such commercial pleasure gardens, but this zone was also where many orphan asylums, hospitals, insane asylums, almshouses and prisons were relegated. In other words, west of Broad was way out of town and thus out of the sight and mind of decent folks who lived, even in the 1830s, within just ten or twelve blocks from the Delaware River. You only dared west of Broad, if you were passing through to locales farther west or if you had some unfortunate inmate to visit in one of those gloomy asylums.

Certainly, for a day of rest and recreation outside, Philadelphia’s growing urban population could head to one of William Penn’s city parks. But these were often undeveloped and not as decorous as they are today. Logan Square, for example, was used as a potter’s field and a setting for public hangings until 1825. A rural cemetery, such as Laurel Hill or any of the other out-of-town cemeteries, could surely provide Philadelphians with an environment that was peaceful (in more ways than one), but these burial grounds were often too far from the core of the city.

The better recourse would be to simply make your way past Broad Street for a day at one of the botanical gardens in that part of town. These amusement resorts—which served as the Philadelphia Zoo or Great Adventure of the day—were quasi-public places, some drawing attention to exotic species or particular styles of gardening, while others offered meals and forms of entertainment, such as music, fireworks, and balloon ascensions. Their greenhouses often were stocked with exotics and the grounds were neatly laid out with flowers and fruit trees according to the English way of setting up formal gardens. Many were named after similar places in England and elsewhere. The proprietors knew how to lure people to their resorts.

McArans Pleasure Garden. This drawing of “McAran’s Pleasure Garden” is by Frank H. Taylor, after a painting by David J. Kennedy.

McArran’s (or M’Aran’s) Garden (1839-1842) was located between 17th and 18th Streets alongside Filbert Street (now JFK Boulevard). The 4 acre retreat, more or less on the present site of the Comcast Center and the Arch Street Presbyterian Church, was handsomely laid out and offered a great variety of rare plants. The proprietor, John McArran, had collected and covered his premises with shade trees, greenhouses, and so on. The place was also known for its fine collection of birds; a bald eagle once lived on site.

A botanical gardener and purveyor of seeds as early as 1821, McArran had decorated the grounds of Lemon Hill for Henry Pratt. He specialized in giving his patrons strawberries and cream in the season. John McArran was also a land speculator in regard to his resort property, keen on ultimately making a profit from its sale.

Signor Antonio Blitz, an accomplished 19C magician, performed at McArran’s Garden and later wrote: "I remember [McArran] taking me to look at a field of some acres planted with the trees, and his remarking that he had refused an offer of fifteen thousand dollars for them. I inquired what he expected to receive? He replied “Double that amount!” But his hopes failed for in a few days following, the bubble exploded and he not only lost all he had invested, but seriously involved himself."

Another nearby resort was Smith’s Labyrinth Garden, once between Cherry and Arch Streets and 15th and 16th Streets. The original garden was established by one Daniel Engelman, a florist and nurseryman from Holland, who came to Philadelphia in 1759. Englishman Thomas Smith subsequently acquired the tract and turned it into a place of amusement. Smith was known around Philadelphia for his accurate meteorological observations and record keeping.

The compilers of Philadelphia in 1830 describe Smith’s Labyrinth Garden as displaying “ingenuity,” meaning that this was indeed an irregular network of passageways that guests could plod their way through. They could even do this at night, for the resort was “usually illuminated nights, and the visitors are entertained with instrumental music.”

In 1830, a curious feat was accomplished at the Labyrinth Garden. A man undertook a walk around the grounds as part of a $1000 bet that he could walk a thousand miles in eighteen days. The task was commenced by one Joshua Newsam on September 30th. The 27-year old fellow walked along a course within the Labyrinth while crowds came to see him, evidently paying for admittance and spending some time at the garden. (Thomas Smith encouraged this challenge because he had witnessed such feats earlier in his life and wanted to revive one of the manly exercises of England.) Starting at 6 am each day, Newsam walked in all weather and pushed out about sixty miles a day. Attributing a leg sprain to all the turns he had to make to stay on the course, Newsam nevertheless completed the exercise in 18 days, having walked a thousand miles and never leaving Philadelphia. He did, however, lose 15 pounds.

The city block-large Sans Souci Garden appears above and to left of Logan Square in this ca. 1837 Map of the City of Philadelphia drawn by J. Simons.

Sans Souci Garden was the largest for-profit botanical haven within the current-day confines of Center City. It boasted a fine hotel at which visitors were furnished with fruit from the garden greenhouses as part of their refreshments. Sans Souci (French: without worry) had been established in 1808, and remained in operation through the 1830s. The garden was respected for its botanical collection; a portion of William Hamilton’s private collection—developed at the Woodlands in West Philadelphia—wound up there.

Sans Souci occupied the entire city block between Arch and Race Streets and between 20th and 21st Streets, now the site of Center City housing and Saint Clement’s Episcopal Church. The resort was also immediately south of the Magdalene Asylum (a private charitable organization for the redemption of prostitutes) and the Pennsylvania Asylum for the Blind—illustrating how such institutions were established outside of the populated sectors of the city.

These 3 tranquil public pleasure gardens were gone by the mid-1800s, as the city grew. The land they occupied in the heart of town became much more valuable by then; housing was generally erected on these practically undefiled properties. Furthermore, the resorts gradually lost their appeal as other types of amusements came to the fore.

Alfred M. Hoffy, lithographer. View of Robert Buist’s City Nursery & Greenhouses. Philadelphia Wagner & McGuigan, 1846.

For-profit botanical seed and nursery gardens also had been established in the surrounding districts of Northern Liberties, Southwark, and Moyamensing in the early 19C too. Buist’s Garden was on Lombard Street, near Tenth, and was run by nurseryman Robert Buist. He began the first commercial propagation and sale of poinsettias. Parker’s Garden was on Prime Street (Washington Avenue) beside Tenth Street had was handsomely laid out with arbors, gravel walks and so on.

The 18C Landreth’s Garden which sold plants and seeds was on Federal Street near the Schuylkill, founded by David Landreth, who in the late 1700s established D. Landreth & Company. His son opened a seed store near Third and Chestnut Streets that sold plants and also started publication of the Floral Magazine and Botanical Repository.

The 18C Gray’s Gardens, a public pleasure garden which had its heyday from 1789-1792, at the Lower Ferry over Schuylkill River, was one of the earliest such retreats in the region. All traffic to and from the South passed by this place since it was run by the family that held the ferry concession (and, later, floating bridge) at the spot. On top of being an objective for pleasure trips from town, Gray’s Gardens became a favorite place to welcome guests to Philadelphia. Citizen committees would meet important people there and accompany them to the city. George Washington repeatedly received civilities at what may be called the old gateway into Philadelphia.

This extract from the 1858-1860 Philadelphia Atlas by Hexamer & Locher shows the orderly grounds of the remaining part of Vauxhall Garden at the northeast corner of Broad and Walnut Streets. The Garden originally took up the entire city block (to Juniper Street). Right at the intersection is the Dundas-Lippincott Mansion (the “Yellow Mansion”).

Remarkably, the 18C Bartram’s Garden, where plants & seeds were sold worldwide, remains on the west bank of the Schuylkill to this day. In fact, Bartram’s once advertised that “railroad cars to Wilmington pass through the grounds and afford the means of reaching this delightful spot.”

Bartram's Garden in 2012 from bartramsgarden.org

Returning to what was to become Center City Philadelphia, there were several other cultivated open-air areas. The Lebanon Garden, notorious for its popular tavern, opened in 1815 at Tenth and South Streets and exhibited fireworks for years on the Fourth of July. On Fourths of July fireworks were generally displayed. A sign hung in front of the garden with verses on the sign. On the east side was inscribed;

"Neptune and his triumphant host

Commands the ocean to be silent,

Smoothes the surface of its waters,

And universal calm succeeds."

On the opposite, or west side, was the following:

"Now calm at sea, and peace on land,

Has blest our continental shores;

Our fleets are ready at command

To sway and curb contending powers."

Over the old Lebanon Garden Tavern were these lines:

"Of the waters of Lebanon

Good cheer, good chocolate and tea,

With kind entertainment

By John Kenneday."

The inauguration of General Andrew Jackson as President was celebrated at the Lebanon Garden in 1829, "by an old-fashioned bear-roasting & the destruction of other eatables...The old Lebanon at that time was kept by the late Captain John Pascal, & the day passed off without anything to mar the pleasure of the occasion...A buffalo's tongue was prepared & smoked & sent to General Jackson by Captain Pascal. A buffalo was bought by him from a well-known butcher at that time named Charles Pray. It came from the West with a drove of cattle, & 70 dollars were paid for it. It was penned up at Old Lebanon, & fed on hay & a bushel of potatoes daily. On the day before the barbecue several hundred persons congregated to see the fun. A stout rope, about 150 feet long, was made fast in the middle to the horns of the beast, & about 50 persons took hold of each end & drew him back in the garden, which extended to Shippen street from South street. A ring had been made secure to the centre tree of 3 old cherry trees, in a row running east & west. The end of the rope was passed in & gradually drawn through the ring by the persons alternately letting go as they got to the ring, & exchanging their hold to the end which had passed through it. Both ends were finally made fast to the next trees. A Mr. Peal, who had frequently shot buffaloes on the prairies, stood 20 yards off & shot several times at the animal, aiming to strike him behind the fore shoulder. At each shot the buffalo merely gave a shudder. This Mr. Peal thought strange, & then he shot him in the head, which he did not wish to do for fear of destroying his skin, desiring it as perfect as possible, to have it prepared for Peale's Museum, where, indeed it finally was placed, & a bunch of candles hung at the side made of the fat of the said beast . After having been shot in the head the animal fell on his knees & rose several times. Fearing the possibility of his breaking loose, he was knocked in the head with a butcher's axe & killed. On the northerly tree the heart was hung up, exhibiting the holes made by the bullets, each one having passed through it. The tongue was prepared & smoked, & packed in a polished hickory box, in hickory shavings made for the occasion, resembling curled ribbons, by Henry J. Bockius, carpenter, & was sent to General Jackson. A bear was also killed, & roasted whole on a windlass such as was also built for the buffalo. Fires were kept up with pine & hickory wood all the night before."

Three blocks up on South Street, at Thirteenth Street, was Hibbert’s Garden, with its superb collection of dahlias and japonicas.

The Tivoli Garden, on the north side of Market Street between Thirteenth and Centre Square, first opened in 1813 as the Columbian Garden. Besides the other pleasure garden enticements, it offered a “summer theatre” for pantomimes and light acting, such that it eventually became a theatrical center of some importance. And from 1800 to 1818, Fouquett’s Garden, between Tenth and Eleventh and Arch and Race Streets, sold guests mead and ice cream.

The Lombardy Garden opened about 1800 on the west side of Centre Square, at Fifteenth and Market Streets. The garden derived its name from a group of Lombardy poplars planted around there by William Hamilton, when Centre Square was the location of the city’s first waterworks. The proprietor, one James Garner, provided breakfast and turtle soup for his patrons. Concerts, fireworks shows and circus-like exhibitions were held there amid the poplars and the serpentine gravel pathways. The Lombardy Garden apparently lasted until 1830, when it was reopened as Evans Garden.

For six additional years, the First City Troop used the Evans Garden for its drills and their place of assembling. In the summer of 1828, they went on an encamping excursion to Yellow Springs, Chester County. They invited Frank Johnson, the celebrated African American musician, to perform on his bugle, while the Troop were preparing to depart...On that excursion the Troop assembled in the garden with over 80 equipped men, plus a few other "invited" gentlemen. Singers at the Chestnut Street Theatre were heard at Evans Garden on summer evenings. The property was sold for residential development in 1836.

The Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden, Philadelphia. Lithograph by B. Ridgeway Evans.

One of the last gardens opened was the Chinese Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden in 1828, on the rising ground northeast of where the Philadelphia Art Museum is today. The buildings were designed by John Haviland and the pagoda was 100 feet high, providing a splendid view of the Schuylkill River. Unfortunately, the roads to this resort from town were usually in bad condition, so the enterprise was not a success.

Vauxhall Garden was perhaps the most celebrated pleasure ground in Philadelphia. The place went into operation in about 1814 on the city block between Walnut and Sansom and between Broad and Juniper Streets. The ground had been originally been owned by Colonel John Dunlap (of Revolutionary War fame) and David Claypoole (of the publishing firm of Dunlap & Claypoole). It was Dunlap who embellished the place with choice trees, flowers, and graveled walks.

Named after London’s famed pleasure garden, Vauxhall (1813-1819-1838) also had a dancing-room large enough for balls, which must have helped make it the most fashionable of all Philadelphia’s pleasure gardens. Indeed, Vauxhall was touted as the most beautiful summer resort in the United States and visitors described it as “a little paradise.” Admission on days offering music was 50 cents, with 25 cents returned in the form of refreshments. Illuminated with “variegated lamps” at night, the venue featured fireworks, hot air balloon ascensions, and parachute leaps from those balloons...

On the evening of September 8, 1819, Vauxhall Garden was destroyed by a mob that took offense at a postponement in the presentation of a balloon ascension. (The balloon itself was ripped to shreds.)...One observer recounted, "one of the high constables of the city, rushed into the room and informed Mr. Wharton that a terrible riot and fire were in progress at the Vauxhall, caused by the failure of a balloon ascension. The company at once left for the garden. On approaching Thirteenth street the (old) elm tree was discovered on fire. They all hurried into the enclosure. Several arrests were made of the rioters, and the disturbance was quelled, but not until much damage was done."

The place reopened as the Vauxhall Theater and persisted as a summer stage and open space for a number of years. The Marquis de Lafayette was feted there with a grand banquet in 1825. The elderly general was received at the entrance by one hundred little girls all dressed in white.

The theater was demolished in 1838, and Scottish millionaire James Dundas built the famed “Yellow Mansion” at the intersection of Broad and Walnut. Designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, the great house was the scene of many of social events in Philadelphia. The mansion’s charming garden along the east side of Broad Street was actually part of the old Vauxhall Garden. President McKinley reviewed the troops from a grandstand in the garden during the 1898 Peace Jubilee celebrating the end of the Spanish American War.

Frank H Taylor The-Yellow-Mansion a.k.a. the Dundas-Lippincott Mansion, showing some of the remaining Vauxhall property. This early 20C print was drawn by Frank H. Taylor. Detail

It’s too bad that all of these money-making resorts are long gone. Then again, Bartram’s Garden is still around and can today give us the very same pleasure that the botanical gardens of the early 19C gave Philadelphians back then. Still, we sure could really use a nice garden in Center City, maybe with an ingenious labyrinth and leaps from hot air balloons.

About the guest author:

Harry Kyriakodis, author of Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Northern Liberties and The Story of a Philadelphia River Ward, regularly gives walking tours and presentations on unique yet unappreciated parts of the city. A founding/certified member of the Association of Philadelphia Tour Guides, he is a graduate of La Salle University and Temple University School of Law, and was once an officer in the U.S. Army Field Artillery. He has collected what is likely the largest private collection of books about the City of Brotherly Love: over 2700 titles new and old.

.jpg)